The American Steel “Crisis” – An Overview

American steel mills have faced hard times since

1998. In the wake of the Asian financial

crises, rising imports have taken market share from domestic steel producers. Industry profits have declined. There has been a substantial decrease in

steel industry employment and 33 businesses, including some of the largest,

have been forced to file for bankruptcy protection.

The American Iron and Steel Institute and the United Steelworkers

of America (USWA) have urged the President and Congress to enact quotas and

tariffs of 40 percent on foreign imports of steel. In 2001, the U.S. International Trade Commission

(ITC) undertook an investigation to ascertain whether or not illegal dumping

had caused substantial injury. The

trade was deemed unfair and remedies, including antidumping (AD) and countervailing

duties (CVD), were imposed under Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974[1].

Prior to the Section 201 case, 159 antidumping and

countervailing duty cases had been filed and more than three quarters of steel

imports were under controls. Despite

existing actions, the steel lobby was able to proceed with Section 201 filings

and, October 22, 2001, after

many unrelated products were grouped together under a single vote, the ITC

ruled that domestic steel mills were eligible for further action. In response, the European Union, Japan,

Russia and China

have filed complaints that the actions proposed by the ITC are a violation of the

rules of the World Trade Organization.[2]

The U.S.

steel industry claims these actions will level an unfair playing field, save

thousands of U.S.

jobs, and remedy the problems of overcapacity caused by subsidies given to

foreign steel industries. A portion of

the steel industry is seeking additional government intervention in the form of

assumptions, guaranties and bailouts of under-funded retirement plans.

An Overview

of Trade Restrictions

For reasons of national security, health, economy or other interests,

every government controls imports.[3] Acting on behalf of American citizens, the

U.S. government monitors, inspects, records, taxes, limits or reserves the

right to refuse virtually every item to cross its borders. In fact, the U.S.

government attempts to use trade restrictions to influence the trade policies

of foreign governments all over the world, attempting to prescribe a morality

that more closely represents the American norm, or to offer protection from

competition to American businesses, industries and individuals.

The most direct method of protection available is

placement of restrictions on the quantity, quality or class of commodity being

imported for consumption. These import

controls are barriers to trade. They may

be in the form of simple tariffs that increase the price of a particular

import, therefore reducing its appeal, or in the form of quotas to limit the

quantity of a particular item competing with domestically manufactured

goods. Tariff quotas, like those applied

to U.S. steel

imports, allow a set quantity of goods to enter the country and then levy a

duty on further imports of the selected good. These controls are intended to

benefit domestic consumers or punish exporters.

General Problems of Control

The design of the American system gives the authority to

make many of the most important economic choices, including import controls, to

elected or appointed representatives who may not always have the best interests

of the represented citizens in mind at the time the decision is made. These officials are influenced by their own

ideals, pressure from their directors and constituents, influence by political

action committees, experts who work in the field being studied and protected,

and foreign interests.

The decisions made by our representatives may have

little effect or, in addition to achieving, or not achieving, the goals stated,

they may have unintended impacts on people and industries never

considered. To further complicate the

decision process, the decision maker often does not answer directly to those

most affected by the choices made. Commissioners of the U.S. International

Trade Commission are nominated by the President of the United

States for 9-year terms and must be

confirmed by the U.S. Senate. There may

be no more than three persons of any one political party seated at a given time[4]. ITC commissioners are not elected by U.S.

citizens and, with a 9-year term, may not even represent the current political

view of Americans.

There is, in a broad sense, no way to gain more of one

thing without giving up something else. This

may be an exchange of time, money, a product or service, or a future debt. The job of any party that wants to better its

position is to discover the choice that yields the greatest benefit for the

costs incurred. This choice is

unavoidable and made difficult by the problems of analyzing the situation. The problems of analysis include a lack of

information that is complete, accurate and timely and the difficulties of

complete and impartial analysis of this data. Information is itself a scarce

and valuable resource and great costs, in the form of time or money, may be

incurred in its acquisition. [5]

The Current Steel “Crisis”

The History of the American Iron and Steel

Industry

Iron and, later, steel have been used for 5000 or more

years. Iron was smelted and wrought in Mesopotamia

and cast in ancient China

using primitive wood burning furnaces.

The technologies used changed little for four millennia until the desire

of people to perfect new iron and steel using technologies led to innovations

in the smelting processes during the 15th century. The new blast furnaces allowed the

manufacture of better guns. Directly or

indirectly, steel has had significant impact on world affairs. Wood for these

furnaces eventually became scarce and, in 1709, it was discovered that coke, a

form of coal that burns at very high temperatures, could be used for iron ore

processing. This was the birth of the

integrated mill. In the last two centuries, performance of the technologies has

improved, but the underlying technology in the iron industry has changed little[6].

The steel making process has changed dramatically in the

past 150 years. With every change,

productivity has increased. The mid

1800s saw the introduction of the Bessemer converter processes, which were

replaced by the open hearth process and electric arc furnaces (EAF) at the turn

of the 20th century. The open

hearth was favored in the United States

for its flexibility and improvements in the quality of the steel produced. The last Bessemer converter was finally

abandoned in Pennsylvania in

1969, having been superceded by the basic oxygen furnace (BOF), which was

introduced in 1954. No new open hearth

furnaces have been built since 1958 and the last one in domestic operation

closed in 1991.[7] The extinction of the open hearth furnace in

1991, and its previous decline, corresponds to a notable shift in the mix of

production processes used in the steel industry and the timing of our current

crisis.

Current State of Affairs in American Iron and Steel

|

Bankruptcies

in the U.S.

Steel Industry[8]

|

|

Company

|

Employees

|

Status

|

|

A1 Tech Specialty Steel Corp

|

790

|

Emerged

|

|

Acme Metals

|

1,700

|

Closed

|

|

Action Steel

|

140

|

Operating

|

|

American Iron Reduction

|

70

|

Closed

|

|

Bethlehem Steel

|

13,000

|

Operating

|

|

Calumet

|

210

|

Closing

|

|

CSC Ltd.

|

1,225

|

Closed

|

|

Edgewater Steel Ltd.

|

140

|

Closed

|

|

Erie Forge & Steel

|

300

|

Operating

|

|

Excaliber Holdings Corp.

|

800

|

Operating

|

|

Freedom Forge Corp.

|

1,120

|

Operating

|

|

GalvPro

|

60

|

Closed

|

|

Geneva Steel Co.

|

1,600

|

Closed

|

|

Great Lakes Metals LLC

|

40

|

Closed

|

|

GS Industries, Inc.

|

1,750

|

Operating

|

|

Gulf States Steel

|

1,906

|

Operating

|

|

Heartland Steel Inc.

|

175

|

Operating

|

|

Huntco Inc.

|

553

|

Closed

|

|

J&L Structural Steel Inc.

|

275

|

Operating

|

|

Laclede Steel Co.

|

1,475

|

Emerged

|

|

LTV Corp.

|

18,000

|

Closed

|

|

Metals USA

|

4,700

|

Operating

|

|

National Steel

|

9,283

|

Operating

|

|

Northwestern Steel & Wire

|

1,600

|

Closed

|

|

Precision Speciality Metals Inc.

|

200

|

Operating

|

|

Qualitech Steel SBQ LLC

|

350

|

Closed

|

|

Republic Technologies

|

4,600

|

Operating

|

|

Riverview Steel Corp.

|

60

|

Operating

|

|

Sheffield Steel

|

610

|

Operating

|

|

Trico Steel

|

320

|

Closed

|

|

Vision Metals Inc.

|

610

|

Closed

|

|

Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel Corp.

|

4,800

|

Operating

|

|

Worldclass Processing Inc.

|

80

|

Emerged

|

|

Bankruptcies 1997 – March,

2002

|

According to the American Iron and Steel Institute, the

U.S. steel industry has the best labor productivity in the world and, while its

prices are among the lowest available to U.S. markets, restricted foreign

markets, dumping and excess capacity have treated the U.S. steel industry unfairly.[9] It is also claimed that as many as 350,000

American jobs will be lost if unfair trade practices are not quickly remedied.[10]

Finally, steel industry employees, members of the USWA, were urging the

President to impose 40% tariffs on steel imports.[11]

In all industries, excess capacity and over production

reduce prices. This is a function of

supply and demand. U.S.

prices for steel are at 20-year lows and companies representing 30% of American

capacity have filed for bankruptcy.[12] The U.S. steel industry, in the period

spanning 1986 to 2000, has increased production faster than the world totals

while experiencing a decline in capacity utilization from 93.35% in 1995 to

79.2% in 2001.[13] The domestic production capabilities exceed

demand for domestic production at the prices offered. When supplies exceed demand, prices fall.

(A

note about data)

(A

note about data)

Not only has domestic

production been increasing faster than the world production, but U.S. capacity has been increasing faster than production.

Domestic supply was also increased between 1997 and 2000

by a series of eight suspension agreements. The International Trade

Administration (ITA), a branch of the Department of Commerce, by accords with

previously restricted steel exporters, reached favorable agreements about

pricing and quantities available for U.S.

import. The countries affected included Brazil

in July 1997 and China,

Russia and Ukraine

in November, 1997. By shear volume,

though, these suspension agreements are dwarfed by the AD and CVD that were

already in effect at the end of 2001.

The ITA maintains a list of CVD and AD orders, and of the 263 AD and 51

CVD orders on their list dated March 15, 2002, more than half were directed at

steel and steel products.[14] Interestingly, these active measures are

against the same countries from whom the steel producers are seeking new

protection.

One of the reasons capacity has outstripped production

is that Big Steel has invested significant capital in EAF shops in an attempt

to compete with mini-mills. When the

1998 steel crisis began, Acme Steel was in the midst of bringing a new

thin-slab mill on-line. Increased

availability of inexpensive imports coupled with start-up production problems

left them scrambling to cover fixed costs.

Geneva Steel was in the midst of efforts to modernize and was deeply

affected by cash flow problems.[15] Surprisingly, even with slumping demand for

their products and financial losses, U.S.

producers have continued to bring new production on-line. The industry had losses

in 1999 of 464 million dollars and one billion dollars in 2000, but still found

it prudent to invest in 3.8 billion dollars worth of new assets.

Another problem of integrated steel mills are the

so-called legacy costs. While

manufacturers in the European Union were retooling and streamlining their

operations, the big mills in the U.S.

were signing new contracts with their unions. They offered lucrative benefit packages in

exchange for lower wages. When they finally

headed the warnings about mini-mills being their biggest competitors, it was too

late. They had offered generous

compensation packages in the 1980s while significant import protection shielded

them from overseas competition and they thought the money to fund retirement

packages would be there when they needed it.

Now that they are in dire financial straights, they are unable to

complete merger talks because of astronomical legacy costs, specifically 7.7

billion dollars in pensions that were not sufficiently funded and an additional

sum for healthcare costs and workers’ compensation in the range of 5.5 billion

dollars.[16] The federal government declined, for now, to

guarantee these obligations, knowing that the real cost could be greater than

20 billion dollars. Were it not for these unchecked problems of the past,

profitable companies might be able, through mergers and acquisitions, to save

American jobs.

Recent Trends in the Structure of the Steel

Industry

The 1960s and 70s saw major advancements in electric arc

furnaces, but Big Steel continued to build BOF shops until 1991. EAF shops did not become popular and

widespread until they proved they could produce consistently high quality sheet

steel. Many integrated mills completed

their own EAFs in the mid 1990s.

These EAF shops, which use scrap or recycled metals as

their inputs to production, are commonly called mini-mills, though some are

larger than their integrated predecessors.

This is because, unlike the fully integrated steel mills, EAF shops have

no need to produce coke. Because of

their size, the production lots are typically smaller than integrated mills,

making it economically feasible to produce smaller production runs and

specialty steels. The long established

industry leaders in the US

have been entrenched in mass production for economies of scale that are no longer

required by mini-mills to remain profitable.

Presently, although electric arc furnaces are gaining share, BOF shops

continue to account for more than half of US steel production.

In member countries of the Organization for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD), there have been dramatic changes in the

way business is conducted, most notably the shift to electric furnaces, new

technologies in continuous casting, and exponential increases in

efficiency. The type of person employed

in the steel industry has changed as a result of the different responsibilities

assigned to the workers. This puts a new

face on steel.

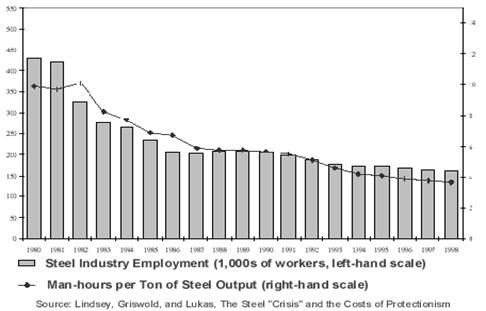

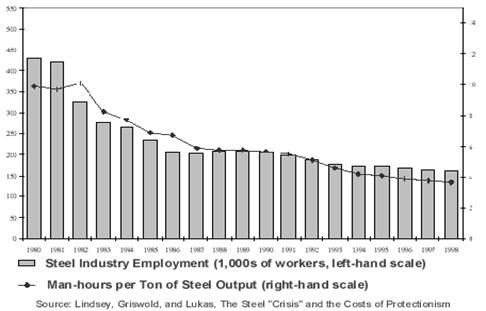

In the 15 years ended in

2000, the U.S.

steel industry has seen a 43 percent decrease in the average annual number of

employees and, for the same period, an increase in production of 37.5

percent. This is a result of changes in

employee type and motivation as well as technological advances and increased

efficiency. The average rate of annual

decline for the 10 years 1986 to 1995 was 3.8 percent and the average annual

decline in employment for the five years 1996 to 2000 was only 4 percent. These small percentages hide the numbers of

employees affected. In 1986, the industry

employment was 174,783, with a total employment cost of $8.38 billion. In 1995, steel employed 122,613 at a cost of

$9.48 billion. In 2000, 99,536 employees

cost the industry $8.2 billion for an average employee cost of $82,372 each. Certainly, this does not represent the

average steel worker, as these figures include all the industry executives, but

the AISI published reports showing employment costs of wage earning and

salaried employees including overtime and benefits show that hourly wage

earners have an average annual cost of about $80,000 each in 2000. If trends continue, the hourly cost of

employing an average steelworker could reach $50 per hour by 2007. It is

estimated that, while the cost of employing a steelworker’s job is high, the

cost of saving the job could be 732 thousand dollars.[17]

|

Industry

|

Total Hourly Compensation for 2001

|

As a percentage of Steel

|

|

Steel

|

$37.91

|

100%

|

|

All Private Workers

|

$20.81

|

54.9%

|

|

Construction

|

$24.08

|

63.5%

|

|

Manufacturing

|

$24.30

|

64.1%

|

|

Services

|

$19.74

|

52.1%

|

Outside Factors of Influence

Another factor affecting steel prices has been the

Asian financial crisis. The relative

strength of the U.S. dollar compared to the currencies of many exporters has

allowed the U.S.

steel consumer to purchase the same quantity and quality of product at the same

home price for fewer U.S. dollars.

Exchange rate benefits are an advantage to purchasers yet are viewed as

illegal dumping by producers. It would be foolhardy for any manufacturer to

intentionally overlook a commodity purchase at a lower price if the delivered

quality is the same. Even if a foreign country is willing to sell a product for

less than it costs to make, there should be no resistance. Of particular

concern to steel producers in the beginning of the crisis (mid 1998) was the

price of high quality Japanese hot rolled steel. It was available to American

purchasers near the price of Russian steel, a lower quality product.[18]

In July of 1997, the U.S. dollar purchased a little more

than 115 Japanese Yen, but in July of 1998, one dollar could buy almost 141 Yen. The situation was the same for Korean

producers. The dollar bought 893 Korean Won

in July of 1997 but 1296 Won only one year later. The purchasing power of steel consumers

desiring Japanese and Korean steel had increased by 22 and 45 percent in only

one year. While bad for the domestic

steel producers, this was very good for steel users. Steel users include the steel industry which

purchased, excluding pig iron, 30 percent of America’s

steel related imports for further processing and resale.[19] A decline in the price of inputs should lower

retail prices and increase consumer demand.

Import Increases for Selected Regions [20]

|

Product Group

|

Net

Increase in U.S. Imports 1997-1998 (metric tons)

|

Increase

in U.S. Imports from Japan, Korea, and Russia 1997-1998 (metric tons)

|

Import

Increase from Japan, Korea, and Russia Over Total U.S. Import increase

|

|

Total Steel Mill Products

|

9,401,264

|

7,129763

|

76%

|

|

Finished Steel

|

9,022,490

|

7,690,081

|

85%

|

|

Hot-Rolled Steel

|

4,515,274

|

3,528,111

|

78%

|

|

Cold-Rolled Steel

|

355,290

|

485,715

|

137%

|

|

Cut-to-Length Plate

|

668,349

|

416,180

|

62%

|

|

Heavy Structurals

|

1,585,173

|

1270,203

|

80%

|

|

Rebar

|

478,900

|

565,909

|

118%

|

|

Line Pipe

|

309,952

|

310,226

|

100%

|

In Asia, the problem was made

worse by a massive decrease in local demand.

In the midst of a major financial collapse, new construction was

extremely limited, which made foreign exports appropriate. At the same time, Russia,

which had been supplying the Asian market, found that demand for its product was

higher in the U.S.

than Asia.

The Asian financial crisis can be seen as a direct

contributor to the problems of the American steel industry. The reasons were not intentional but were

rather a function of the free market President George W. Bush cited as an

important part of the plan to encourage economic growth. The American Iron and Steel Institute, while

asking for direct and indirect subsidies from the American government and

American consumers, presents the following:

“…subsidies continue to distort

world steel trade, harming U.S.

producers and workers. Subsidies given to the steel industry sector worldwide

have exceeded government assistance to any other industrial sector. … The

Korean government has provided over $6 billion to the now bankrupt Hanbo Steel

Company. The resulting scandal has made Hanbo Steel one of the worst examples

of the Asian economic crisis and why it exists.”[21]

The American Response to the Steel “Crisis”

Increased restrictions on foreign imports in the steel

industry were enacted by President George W. Bush on March 5, 2002.

In a press briefing by U.S. Trade Representative Robert Zoellick, it was

stated that “the President believes that free trade benefits America’s

consumers and families and that it’s vital to generating jobs for America’s

workers, opening markets for American products and service, and in spurring

economic growth.” He then stated that

some traditional manufacturing industries are unable to respond as quickly as

desired to rapidly changing global economies and announced a plan to impose

quotas and tariffs of up to 30% on major steel products in an attempt to

strengthen U.S.

steel companies during a period of significant global overcapacity.

Factors Affecting Policy Decisions

In the case of the U.S.

steel industry, it seems important to note that, while profits have been absent

for many of the largest firms, and, while unionized workers are being laid off,

fired or losing their jobs due to bankruptcies, they have had money for other

things. They have been purchasing

political influence.

Between 1991 and 1997, the Big Three automakers

(Chrysler, Ford and General Motors) and the steel industry contributed 5.7

billion dollars to representatives in the U.S.

government. General Motors has since

quit making and spoken out against “soft money” contributions. The Big Three contributed money intended to

influence decisions that may have been good for U.S.

citizens, but bad for steel and automakers.

It appears that their influence helped create a pause in the Corporate

Average Fuel Economy standards. Had Congress

decided to continue raising the standard, there would have been costs and

benefits. Automakers would have had to swallow large research and development

expenses to increase fuel efficiency. Steel manufacturers might have lost more

of the automobile market to composites, plastics and aluminum. The average

American family could have saved $544 (54.4 percent of average expenditures)

per year in gasoline expenses[22],

although there possibly would have been a significant increase in automobile

costs.

During the 1997-98 election cycle, 3.2 million dollars

were contributed to Democrats by steel companies and the USWA. As an illustration of the anticipated effect

of contributions, Republicans received 4.2 million dollars from the oil and gas

industry[23]. The Republican Party has strongly supported

the oil and gas industry, both in moves to lower crude oil prices and to open

for exploration the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge. The ITC, currently 60 percent Democratic due

to a vacancy that had not been filled as of April, 2002, has ruled in favor of

the steel industry in Section 201 proceedings.

Big Steel is a general term applying to the large

integrated steel mills, including recently bankrupt LTV, Geneva,

and Bethlehem, the USWA, U.S.

Steel, the American Iron and Steel Institute, and others. Big Steel has been very active in American

politics. It hires and pays former

elected officials with strong governmental ties to gain influence in ongoing

actions and decisions of federal and local governments. The American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) is

a primary source of reference data in the steel industry. It provides statistics, data and analysis for

organizations generally considered to be objective sources of information

including the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Census Bureau, and the Environmental

Protection Agency. The influence of Big

Steel and its representatives, after making nearly 14 million dollars of

lobbying expenditures in 1997 and 1998, exerted pressure and helped to kill the

Multilateral Steel Agreement in the 1990s.

It did this to prevent loss of control of the timing of pending

antidumping petitions. It has also been

the key player in advertising and building public sympathy for the American

Steel Crisis over the last few years.[24]

While AISI is certainly the most complete and

comprehensive source of data regarding the steel industry, it might not be

completely reliable. In December of

2001, the public information on their website contained a wealth of historical

data available with a simple mouse click.

As March 2002 approached, historical data (useful in trend analysis)

became limited, showing only recent data that helped make the case for trade

restrictions. Other factors contributing

to the difficulty of analysis are a change from SIC coding to the new NAICS

system and data that was previously freely available became available only for

purchase from the new publication store.

The historically published data retrieved from

microfiche at the Dallas Public Library, revealed discrepancies that were not

obvious, but that had significant impact on the data presented. It seems that, while heavily promoting a

steel crisis and the problems of a trend of increasing imports as a percentage

of shipments, they have systematically presented misleading information on

their most public source of data: www.steel.org. Changes and corrections to annual data are

expected with time, but in the case of AISI, every annual statistic set

includes preliminary current year data (shipments understated) and corrected

previous year data. The net effect is

that their annual trend analysis always gives the appearance of a larger than

actual percentage representation of imports related to U.S.

supply. These annual indicators are not

corrected when then annual data are updated.

Surprisingly, this is the data most often cited by news sources touting

government action on behalf of the steel industry.

What are the Real Problems in the U.S. Steel Industry?

Proponents of trade restrictions under Section 201 have

indicated that preventing illegal dumping by imposing tariffs on imports would

save thousands of steel-related jobs.[25] The reality is that tariffs or restrictions

will not save jobs.

While arguing for protection from competition to save

jobs, the steel industry has embraced the concept of comparative

advantage. It has begun outsourcing the

jobs and functions of longtime steelworkers like metallurgical, engineering and

market research to experts in those fields outside the steel industry.[26] At the same time, it is trying to prevent

downstream purchasers from doing likewise.

It wants to seek new ways to cut costs, but does not want steel

consumers to have the same privilege.

As shown previously, employment in the U.S.

steel industry has been declining for fifteen years.[27] Even with the newsworthy bankruptcy filings

of LTV and Geneva, who have idled,

but not released 20,600, employees[28],

and approximately 30 other steel manufacturers, the American Iron and Steel

Institute shows that most industry attrition has occurred because of factors

other than the import crisis.

Integrated steel mills have been able to offer

copious compensation packages to their employees because, over the last three

decades, their profits have been protected from foreign competition by a series

of import controls. In the ten year period spanning 1972 to 1981, wages in the

steel industry almost doubled while productivity for the industry as a whole

declined[29]. The large integrated mills tend to have

collective bargaining agreements with employees who are compensated based on contracts

rather than performance. There has been

no need for the individual employee to strive for increased profitability or to

seek innovations in their highly specialized positions. The reality is that often ideas or proposed

changes are met by resistance from supervisors because they might harm the

union’s position in the next bargaining round.

Earlier statements about increased productivity must

now be addressed. In 1980, steel

produced domestically required inputs of approximately 10 man hours per ton

(MHPT)[30].

Currently, at some of the most efficient mini-mills, production can be

completed with inputs of less than 2MHPT while the industry average is closer

to 4MHPT. The large manufacturers with

aging equipment need to invest large sums of capital in either new equipment or

new techniques of manufacturing to keep up with domestic competitors.

Newer EAF mini-mills have located themselves far

away from the centers of business occupied by integrated mills and have sought

to be near their end markets or near scrap supplies to lower the input and

delivery costs of their products. Rather

than hiring specially skilled employees with integrated mill experience, they

have found it more profitable to train young intelligent employees in a broad

range of jobs to allow their workforce the flexibility to match the needs of

the business. Often, pay is dependent on

performance or plant profitability and innovations reap rewards for the

individuals who propose them. The

integrated mills finally appear to have seen the benefits of the mini-mills

lean and efficient operating styles, but the unions have made it difficult to

for them to respond[31]. These appear to be the difficulties of quick

response mentioned by Robert Zoellick during the Section 201 relief announcement.

Despite the obvious

conditions of the domestic industry and its related internal competition

between integrated and mini-mills, the United Steelworkers Union insists that

restrictions on imports will save steelworkers jobs; but there does not seem to

be a strong correlation between job losses and the quantity of imports as a

percentage of the domestic steel supply.

However, it has been shown that there is a very strong correlation

between MHPT as a measure of production efficiency and the decline in

employment.[32]

Markets and Economies of US Steel

The four largest markets of the US steel industry

are service centers and distributors, construction and contractors, automotive,

and steel for converting and processing.

For the fifteen years ended in 2000, these four main markets have

represented, including exports, industry shipments of 65 percent in 1986 to 70 percent in 2001. Service centers have dominated, averaging

approximately 25 percent of receipts.

Service centers typically add value to purchased steel products by

finishing bulk materials for resale.

This may include complex processing or simply cutting material to the

proper length for use. Service centers

compete directly with steel manufacturers for the finished goods market,

including the automotive and construction industries.

The automotive industry is one of the markets of

greatest concern for iron and steel manufacturers because of prior changes in

domestic policies that had unintended consequences on the steel industry. For 15 years, shipments to the auto industry

have remained fairly constant as a percentage of total steel shipments by

weight, increasing almost 59 percent while the steel industry as a whole grew

by only 26 percent. However, there have

been remarkable changes in the product output mix of the automobile

industry. Production of light trucks has

doubled in the same period, surpassing the output of cars. The effect on the steel industry is notable

because, while automakers are making larger heavier vehicles, their steel

consumption is not increasing proportionally.

Another item of note was a 54 day strike by the United Autoworkers

Association in 1999 that depressed demand for steel in the heart of the crisis.

Changes and Controls in the Automobile

Industry

Corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards were

enacted in 1975 to reduce dependence on foreign oil and to promote conservation

of energy. These measures placed fuel

economy restrictions on manufacturers of passenger cars and light trucks, a

classification that includes sports utility vehicles (SUVs), mini-vans and

pick-ups. The fuel economy requirements

for each class of vehicle were initially very similar, but over time, the

policies became increasingly more stringent for passenger vehicles than light

trucks. This has become known as the SUV

loophole.

The domestic manufacturing response to CAFE

standards was to seek the measure that had the lowest cost to benefits ratio,

which was to build lighter cars. Lighter

vehicles require less fuel for propulsion.

Within three years, as the price of gas rose, the American market saw a

surge in imports, especially from Japan. Japanese vehicles were simply more fuel

efficient. In 1981, voluntary export

restraints (VERs) were implemented to protect the U.S.

auto manufacturers. This protection was

sought at a time when the auto industry profits were sagging, the American

economy was in recession, and interest rates were at 18 percent, causing

general demand to be low.

It is estimated that, during the period of 1986 to

1990, the VER benefited U.S.

firms by 9.6 billion dollars. Because of

price increases in domestic vehicles lacking unrestricted competition and

markups by Japanese exporters, the American consumers not only paid for the

increased U.S.

profits, but also for the excess profits of the Japanese automakers. Excess

profits resulted from changes in the Japanese marketing mix. While the Japanese

were limited by the quantity of automobiles they could send to the U.S.,

they were not limited on the type. They shipped

fewer economy cars and more high end or luxury vehicles. These costs totaled 12.4 billion dollars, or,

when coupled with the benefits, a net consumer loss of 2.8 billion dollars.[33] The VERs were eliminated in the early 1990s.

In 2000, CAFE standards were 27.5 mpg for cars and

only 20.6 mpg for light trucks. This may

explain the desire of domestic manufacturers (including some Japanese firms

that moved production to the U.S.

to bypass VERs) to sell relatively expensive SUVs to the American consumer.[34]

Fewer large passenger cars are being manufactured,

in spite of continued domestic demand for large family vehicles. This appears to be an inappropriate response

by automobile manufacturers, and, in a free market, it would be

inconceivable. In a free, competitive

market, producers will produce what consumers demand, at the quantity

demanded. In the American automobile

market, production of too many heavy “gas guzzlers” in a particular class of

vehicles will result in costly governmental sanctions. The American automobile manufacturer has

found a solution in providing large heavy vehicles with all the comforts of a

luxury car situated on a light truck frame.

This package is called the SUV.

Besides changing the market offering, the auto

industry has made another reactive change.

They have begun using higher contents of plastic, aluminum and

composites in the manufacture of new cars to reduce vehicle weight. These material substitutions and decreases in

vehicle weight have two significant impacts.

The first is difficult to measure economically but is significant. According to a study by the National Highway

Traffic Safety Administration, a 100 pound decrease in passenger cars

corresponds to an increase of 302 traffic fatalities[35]. The second effect of decreases in vehicle

weight is a diminished opportunity for domestic steel. While weight reductions are prudent for the

automobile industry, they have a large impact on consumers[36].

Substitutions

Aluminum and composites are relatively more expensive

than steel, which helps maintain the automotive sector as a customer of the

steel industry. Increases in the price

of steel make the aluminum choice more attractive, as one pound of aluminum can

replace two pounds of steel. The effect

is compounded by increased fuel efficiency which means that, over time,

consumers will spend less for fuel. The

AISI contends that the average light truck class of automobiles contains 1,782

pounds of steel at a current manufacturers’ cost of 675 dollars. An increase in price of only 15 percent, or

$101.25 per vehicle, equates to a retail price increase of only .3 to .5

percent of final value[37]. While

these percentages seem like a small price to pay to protect the steel industry,

they equate to a staggering sum in the consumer market. Had this 15 percent

price increase taken effect in 1995, the total cost to consumers in 1999 would

have been more than 5 billion dollars.[38] This amount of money could fund retooling in

the automobile industry which would further impact steel.

Big steel has touted its low Producer Price Index

(PPI) as a justification of government interaction to raise the price of

steel. As we can see from the previous

example, increases in the price of steel can have significant effects down

stream. It is actually the relatively

low PPI that has kept steel as competitive as it is. If the PPI of steel were as high as aluminum,

the steel market would be much smaller than it is today.

Motor vehicle parts have also maintained a

corresponding low PPI and are subject to changes based on the price of their

inputs. Too great an increase in steel

prices might drive automakers more quickly to aluminum, which could have

compounding effects. As the weight of an

engine decreases, the motor supports need to support less weight, which, in

turn decreases the load bearing requirements of the frame. Aluminum is

resistant to corrosion and would certainly be worth considering for

undercarriages.

Conclusions

The U.S. Steel Industry Wants Import Controls

The U.S.

steel industry has experienced tremendous problems. It has felt the effects of a worldwide

recession and has lost market share to low priced imports. Steelworkers are losing jobs while some

businesses close and worldwide overcapacity limits the remainders ability to earn

profits. The industry has benefited from

governmental protection from foreign competition for 30 years and wants more

time to react to a changing marketplace of increasing efficiency.

The U.S. Citizen is Willing to

Allow Tariff Quotas

The American citizen will allow restrictions on imported

steel because voters are unorganized and misled by vocal proponents of

protectionism. The steel industry, having

everything to lose, is willing to spend tremendous amounts of money to

influence trade policy while individuals see very little cost difference in any

given purchase. American society

supports the steel industry’s desire to place the blame for their internal

problems on external sources. American voters do not want to see American

workers lose jobs.

The U.S. Government will Restrict Imports

Government officials will not let the steel industry

die. Not only do officials fear the

repercussions of disappointing an organized voting block, but a concentrated

advertising campaign affects the votes of a sympathetic electorate in a time

when patriotism is high. The USWA

members, former-members and their families represent more than 600,000 voters

in important states. Any move to let the

industry crumble could result in lost elections. Additionally, the best source of information

about the steel industry is the steel industry and the people most qualified to

analyze the data are people with experience in the industry who are sympathetic

to its cause.

We Should Not Restrict Trade in

the Steel Industry

We should not allow restrictions to be imposed on steel

imports. The potential cost to America

includes price increases and jobs lost in other industries. Further, we should not decide legislatively

which businesses should survive and which should not. By imposing tariffs and quotas, we are not

allowing steel users the freedom to find the products that work best for them -

we are legislating which choices they will be allowed to make.

There is no doubt the U.S.

steel industry is in the midst of hard times.

The steel industry of the world, however, is not. Is there really a steel crisis? There are problems of overcapacity, but

capacity problems tend to be cyclic. The

U.S. steel

industry, Big Steel in particular, is in the early stages of making necessary

corrections. There is no long-term benefit to forestall those needed

corrections. While the overcapacity

problems of the steel industry are global, it is not in our own best interest

to decide where the corrections should be made.

Protecting American industry to the detriment of our trading partners

allows our home industry to continue to operate in the same manner that has prevented

it from being able to change as rapidly as necessary.

The American consumer reaps the benefit of depressed

steel prices. While it is popular to

point to foreigners as the cause of jobs being lost, we must not forget the

jobs being saved. For every steel

industry employee, there are more than 20 employees in manufacturing jobs that

depend on steel for their employment. If

we want to save jobs, we should let the steel users get the best prices

available. We cannot save steelworkers

from productivity increases or changes in technology, and we should not pay

more for a product to support featherbedding or pay increases for one of the

highest paid sectors in the country.

Notes and Citations

All steel industry figures not

otherwise credited were compiled from “Annual Statistical Report” American

Iron and Steel Institute, 2000, 1996 (return)

[1]

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, Goodrich, Ben, “Time for a Grand Bargain in Steel?,”

International Economics Policy Briefs 01-9, Institute for International

Economics, http://www.iie.com/policybriefs/news01-1.htm.

under the heading “The Section 201 Investigation” – Most of the information

here is available from numerous reporting sources, but the presentation

here was well compiled and easy to follow, so it has been followed closely

in presentation

[2]

Hufbauer, Goodrich. See above - as the

statements apply also to this paragraph

[3] World Trade

Press, “Basics of Importing, ”

http://www.worldtradepess.com/eit/wfb/ie/153eit.asp

[4] If you

would like addition information about the U.S. International Trade Commission,

you might visit them on the internet at http:/www.usitc.gov

[5] Miller,

Roger LeRoy, Benjamin, Daniel K., North, Douglass C., “The Economics of Public

Issues,” 12th ed

[6] United

States Environmental Protection Agency, “Economic Analysis of the Proposed

Effluent Limitations Guidelines and Standards for the Iron and Steel

Manufacturing Point Source Category,” EPA-821-B-00-009, December 2000 – Most of

the information about the history of the iron and steel industry was obtained

from chapter 2 of this extensive publication.

[7] United

States Environmental Protection Agency,

“Economic Analysis of the Proposed Effluent Limitations Guidelines and

Standards for the Iron and Steel Manufacturing Point Source Category,”

EPA-821-B-00-009, December 2000

[8] United

Steelworkers of America, April 18,

2002, http://www.uswa.org/sra/Bankruptcies032002.pdf

[9] American

Iron and Steel Institute, in the “Facts & Figures” area, http://www.steel.org/facts/power/unfair.htm

[10]

Blecker, Robert A., Ph.D., “Jobs at Risk: The Necessity of Effective Relief for

the American Steel Industry,” http://www.steel.org/images/other/blecker.pdf,

February 2002

[11]

“Thousands from America's Steel Communities Rally at the White House, Imploring

the President to Impose 40% Tariffs on Imported Steel,” News for the United

Steelworkers of America, February 28, 2002, http://uswa.org/press/countdownrallyrelease022802.htm

– Another note from this press release is the quote that “strong tariff remedies … offers the

President a rare opportunity to satisfy the concerns of critical voters by

implementing actions that have been thoroughly documented and advocated by an

independent, bipartisan agency such as the ITC.” If this is not political pressure, I don’t

know what is!

[12] prices

are at 20-year lows in the U.S.

and 30% of the industry, by capacity, has filed for bankruptcy according to U.S.

trade Representative Robert Zoellick in his USTR briefing on steel, March 5, 2002

[13] U.S.

steel production was 10.37% of world output in 1986 and increased to 12.74% in

1996 and has slowly declined to 12.03% of world output in 2000

[14] The ITA

lists 263 AD orders, of which 139 are directed at steel and of the 51 CVD, 30

are against steel. These steel counts do

not include brass, tin or certain consumer products like cookware that are made

of steel! To get an idea about what restrictions are in place, visit the ITA at

http://ia.ita.doc.gov/stats/iastats1.html

[15] “Report

to the President Global Steel Trade: Structural Problems and Future Solutions,”

International Trade Administration, Department of Commerce, July 2000, pg 25

[16] Alden,

Edward, “Washing ton puts high price on steel bailout,” Financial Times,

http”//news.ft.com Feb 13, 2002

[17]

Griswold, Daniel T., “A Wall of Steel,” Center for Trade Policy Studies, http://www.freetrade.org/pubs/articles/dg-7-8-01.html

[18]–

available in its 200 page entirety at http://www.ita.doc.gov/media/steelreport726.html

[19]

Burnham, James B., “U.S. Steel Industry Protection: Bad for America,”

Policy Brief No. 197, McGraw-Hill, 1999,

http:/www.dushkin.com/connectext/econ/ch15/burnham.mhtml

[20]“Report

to the President Global Steel Trade: Structural Problems and Future Solutions,”

International Trade Administration, Department of Commerce, July 2000 – This

table was copied directly from the report on page 192 for its ability to

illustrate the effects of exchange rates.

[21] AISI http://www.steel.org/facts/power/unfair.htm

- they use the statement that subsidies to the Korean steel industry helped

caused the Asian financial crisis as an argument for subsidies to the American

steel industry.

[22]

“Pocketbook Politics: How special-Interest Money Hurts the American Consumer,”

Copyright 1998, Common Cause;

http://www.commoncause.org/publications/pocketbook3.htm Note that the gasoline savings are according

to a Sierra Club study that used CAFE standards of 34mpg for light trucks and

45mpg for automobiles and an average family gasoline expenditure of $1000 per

year.

[23] Bailey,

Holly, “Steeling Tax Breaks: A Battle for Benefits for the Steel and Oil

Industries,” a Money In Politics Alert issued by opensecrets.org on March 8, 1999. http://www.opensecrets.org/alerts/v5/alertv5_07.asp

[24]

Barringer, William H., Pierce, Kenneth J. “Paying the price for Big Steel.

American Institute for International Steel,” Inc.,

http://www.aiis.org/test/four_b.html

[25]

Representatives of the U.S.

steel industry, in a letter to the President of the United

States of America, Dated February 21, 2002,

available for review at

http://www.steel.org/news/pr/2002/images/feb21presletter.pdf

[26]

Barnett, Donald F. “Factors Influencing the Steel Work Force: 1980 to 1995”.

STI Working Papers, 1996/6, OECD, 1996 OECD/GD(96)127 pg12

[27]

Actually, levels of employment have been declining for longer, but the scope of

the data being reviewed and presented start with 1986

[28]

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, Goodrich, Ben, “Time for a Grand Bargain in Steel?,”

International Economics Policy Briefs 01-9, Institute for International

Economics, Table 1, http://www.iie.com/policybriefs/news02-1.htm

[29]

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, Goodrich, Ben, “Time for a Grand Bargain in Steel?,”

International Economics Policy Briefs 01-9, Institute for International

Economics, Table 1, http://www.iie.com/policybriefs/news02-1.ht

[30]

Lindsey, Brink, Griswold, Daniel T., Lukas, Aaron. “The Steel “Crisis”and the

Costs of Protectionism,” Center for Trade Policy Studies, CATO Institute,

http://www.freetrade.org/pubs/briefs/tbp-004.pdf, pg 6

[31]

Barnett, Donald F., “Factors Influencing the Steel Work Force: 1980 to

1995,” STI Working Papers, 1996/6,

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Paris,

1996.

http://www1.oecd.org/dsti/sti/prod/wp_6.pdf, pg 11

[32]

Lindsey, Brink, Griswold, Daniel T., Lukas, Aaron. “The Steel “Crisis”and the

Costs of Protectionism,” Center for Trade Policy Studies, CATO Institute,

http://www.freetrade.org/pubs/briefs/tbp-004.pdf, pg 7, figure 3

[33] Berry,

Steven, Levinsohn, James, Pakes, Ariel, “Volunary Export Restraints on

Automobiles: Evaluating a Strategic Trade Policy, Center for American Politics

and Public Policy,” Occasional Paper series (96-2) Los

Angeles, http://128.97.210.114/paper.htm

[34] Miller,

Roger LeRoy, Benjamin, Daniel K., North, Douglass C., “The Economics of Public

Issues,” 12th ed

[35] Kahane,

Charles J., “Relationships between Vehicle Size and Fatality Rick in Model Year

1985-93” Passenger Cars and Light Trucks, NHTSA Report Number DOT HS 808 570

January 1997, http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/cars/rules/regrev/evaluate/808570.htm

[36] It

should be noted that an effort to reduce injuries and fatalities resulting from

lighter vehicles, air bags have become commonplace. Airbags have become a controversial topic as

there are additional unintended consequences of their use – increased deaths in

collisions that would have otherwise been non-fatal.

[37] “A

Perspective on Steel Prices and Section 201 Relief: Why Temporary Quantitative

Restraints on Steel Imports Will Not Cause Substantial Increases in Steel

Prices,” AISI. http://www.steel.org/policy/pdfs/201PriceImpactcust_rem.pdf,

pg 1

[38]These figures

were derived by multiplying $101.25 by the quantities of light truck vehicles

sold in the US

for the years 1995 to 1999, presented in 1000s:

1995: 5306, 1996: 5448, 1997: 5858, 1998: 6013, 1999: 7025. Data prepared by Institute

of Labor and Industrial Relations

University of Michigan, et al. “Contribution

of the Automotive Industry to the U.S. Economy in 1998: The Nation and Its

Fifty States,” Pg 5, http://www.autoalliance.org/umstudy/umstudy-jan2001.pdf

Copyright 2002 by Jeremy Wanamaker

for more information or comments, please contact

me at jeremy@tiedyeguide.com